Appendix

Appendix A - Notation

The BYOL terminology is used throughout this blog post. To compare to other papers, see the below table.

| Name | SimCLR | MoCo | BYOL (used here) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | |||

| Views | , | , | , |

| Embeddings | , | , | |

| Online Projection | , | ||

| Target Projection |

Appendix B - Data augmentations

Using torchvision.transforms, with inputs crop_size=96 and s=0.5, the color jitter strength, the transform function for training is:

Compose([RandomResizedCrop(crop_size, scale=(0.2, 1.0)),RandomApply([ColorJitter(0.8 * s, 0.8 * s, 0.8 * s, 0.2 * s)], p=0.8),RandomGrayscale(p=0.2),RandomHorizontalFlip(),RandomApply([GaussianBlur([0.1, 2.0])], p=0.5),ToTensor(),Normalize(mean=[0.485, 0.456, 0.406], std=[0.229, 0.224, 0.225])])

The GaussianBlur function applies blur with a radius chosen randomly from the uniform distribution [0.1, 2.0]. See the full code on github.

Appendix C - Deep batch normalization and longer training

In order to more closely reproduce the experimental setup described in the BYOL paper, we ran some longer experiments and tried different hyperparameters.

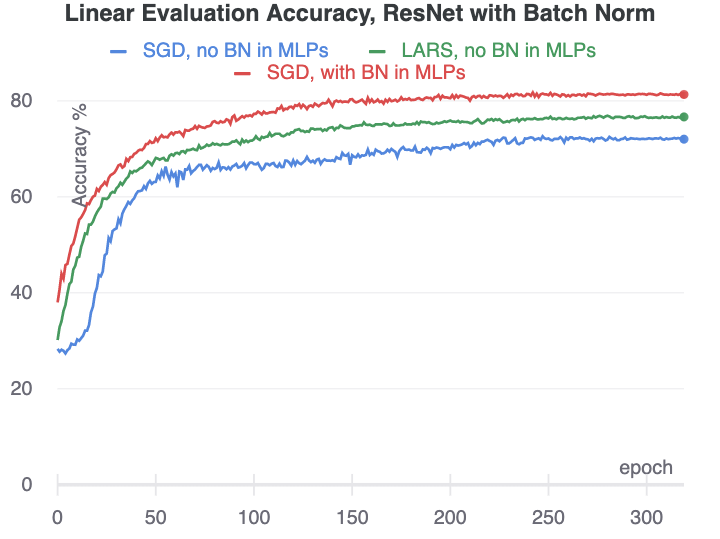

Experiments without batch normalization in the MLPs

We tried a number of longer experiments without batch normalization in the MLPs, to see if under some conditions the network could develop meaningful representations.

First, we simply trained longer with the same SGD optimizer settings. Surprisingly, despite having a collapsed representation at epoch 10, the network is eventually able to eventually move on to a network with higher loss and more useful encodings.

We also tried training with the LARS optimizer used by the BYOL authors. We used the exact hyperparameters reported in the BYOL paper. We were surprised to find that with this set of optimizer settings, there did not seem to be any mode collapse.

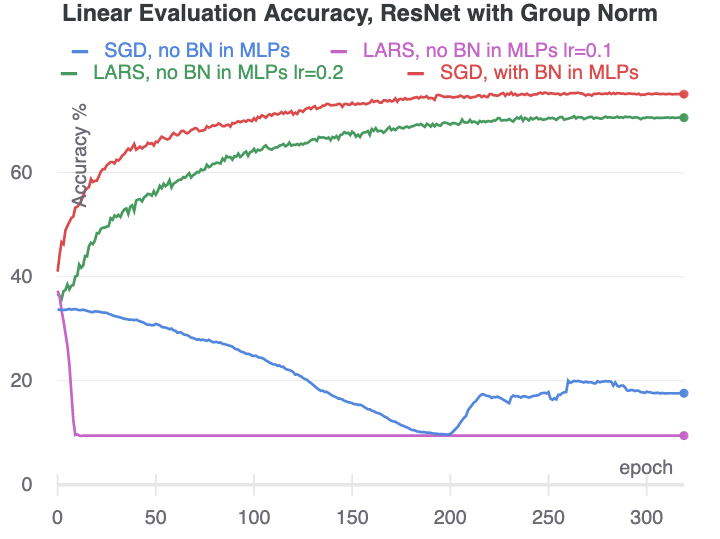

Experiments without batch normalization in the encoder

Although the previous two experiments did not use batch normalization in the MLPs, they still used batch normalization in the ResNet encoder. These earlier batch normalization layers might be the reason the networks do not undergo mode collapse (or are able to reverse that mode collapse). To test this hypothesis, we trained ResNets using group normalization in place of batch normalization. As a control, we trained the ResNet-18 with group normalization with MLPs that do have batch normalization.

For SGD, the results are dramatic: without any batch normalization, the network almost immediately underwent mode collapse and never recovered. Just using the two batch normalization layers in the MLPs prevented this mode collapse entirely.

For LARS with the authors’ learning rate of 0.2, the network recovers from mode collapse fairly quickly and continues to learn a useful representation. However, if the learning rate is reduced to 0.1, the representation collapses immediately and the network does not learn anything. The next section of the appendix explores how LARS avoids mode collapse under certain hyperparameter settings.

Appendix D - Avoiding mode collapse without batch normalization

We found a number of optimization conditions under which networks are able to learn useful representations without any batch normalization. In these cases, the network first learns a collapsed state, and then starts to learn a more useful function. Our overall understanding is that some optimization settings bias the network away from learning functions that produce collapsed representations. Three ways of achieving this bias are weight decay, weight standardization, and layerwise learning rate adaptation.

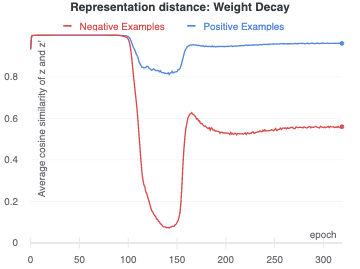

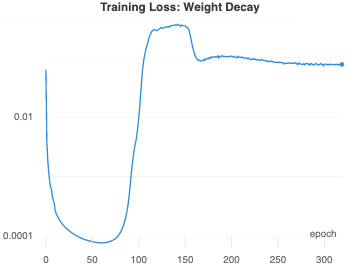

Weight Decay

In some cases, weight decay alone can allow the network to exit the collapsed mode. We found that SGD with a learning rate of 0.2 and weight decay of 1e-5 allowed the network to learn representations that were not collapsed, starting at around epoch 100. We occasionally observed some recovery at a higher weight decay of 1e-4, but at lower or higher values for the weight decay coefficient there was no recovery from the mode collapse. The final representation quality was relatively poor, with a linear validation accuracy at epoch 320 of only 56%.

Our understanding is that in learning the collapsed mode, the network quickly sets a small number of weights to relatively high values. As weight decay brings those weights down over time, the variation in inputs starts to produce output variation, leading to an increase in the training loss. The variation introduced in the output allows the network to start learning more useful representations.

Weight Standardization

Weight standardization is another technique that we have found may prevent mode collapse during BYOL training. Weight standardization ensures that the weights in a network are normally distributed. Implemented with group normalization, this encourages each layer’s output activation to depend on multiple inputs, making the collapsed mode more difficult to learn since there are no large weights or activations.

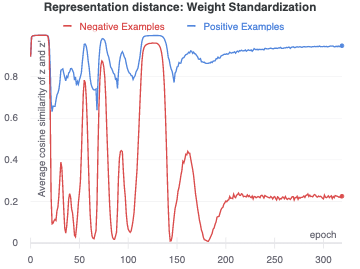

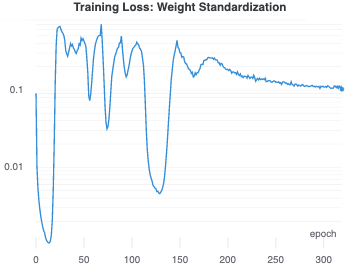

In our experiments, a network with weight standardization and group normalization trained with SGD would usually achieve some sort of separated representation within 100 epochs. However, these representations did not have very good performance overall. In the above example, one can see the network repeatedly try to collapse the representation and then recover again. The final linear validation accuracy for this network was just 51%.

Layerwise learning rate adaptation (LARS)

Finally, we found that the adaptive layerwise learning rate used by LARS was quite effective in producing separated representations given the right optimization hyperparameters. The mechanism for producing bias in the function space is somewhat more complex than the previous cases. It is instructive to review how LARS varies the learning rate for each layer. The local learning rate is defined by,

where is a trust factor, are the weights of the layer, is the loss function and is the weight decay coefficient. This equation shows that the learning rate will be increased if the weights are large or if the gradients are small.

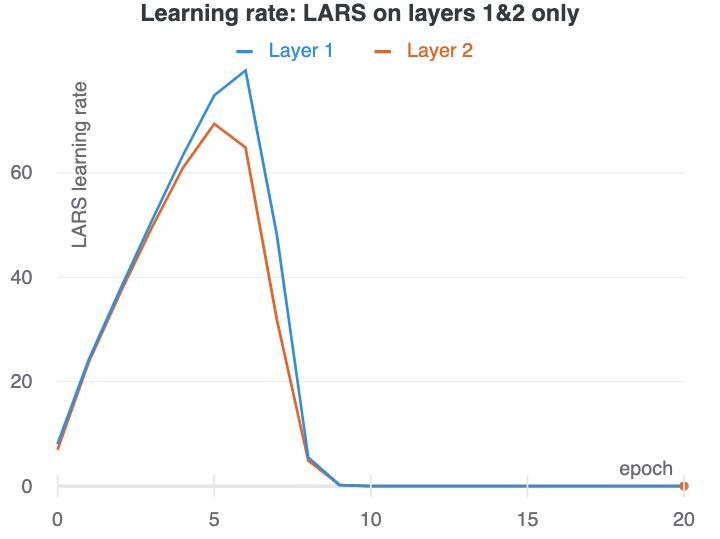

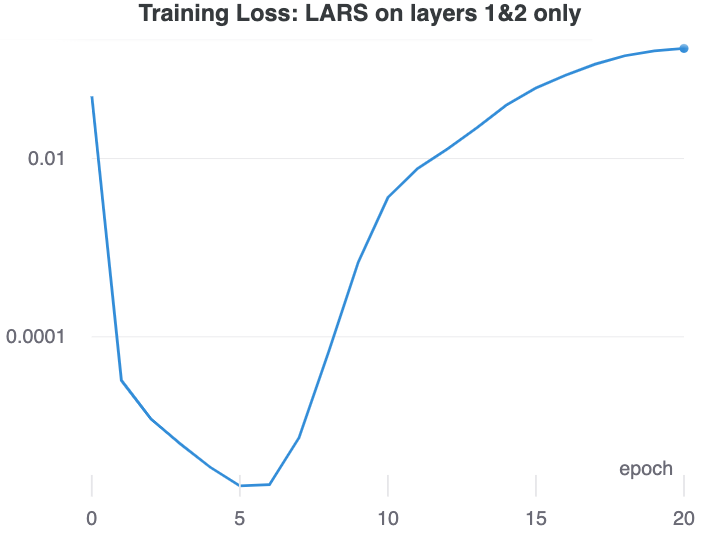

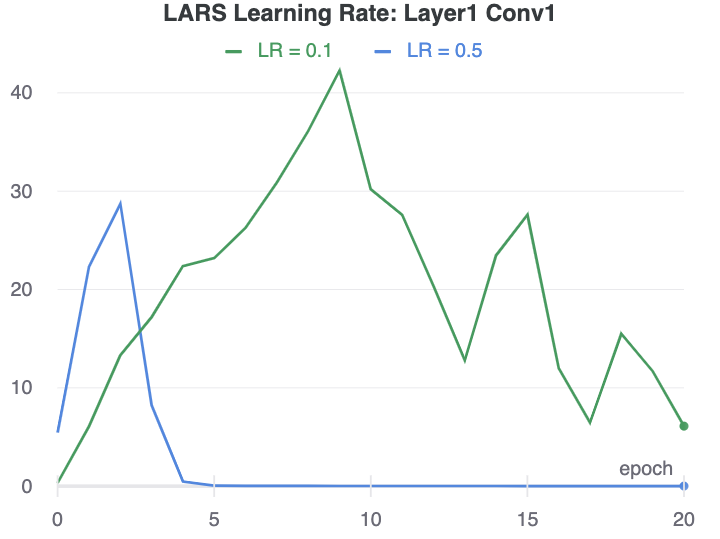

We find that that this layerwise rate scaling in LARS disrupts the ability of the network to remain in a state that produces collapsed representations. As the network collapses the representation, the gradient at the early layers starts to vanish. This makes the LARS learning rate there explode. We have demonstrated this with our ResNet-18 with group normalization by applying LARS to only layer1 and layer2 in the ResNet.

It is not just the higher learning rate, but the gradient dependence of the learning rate that makes LARS successful in avoiding collapsed representations. Our experiments SGD with a higher learning rate on layers 1 and 2 were not able to learn more useful representations after undergoing mode collapse.

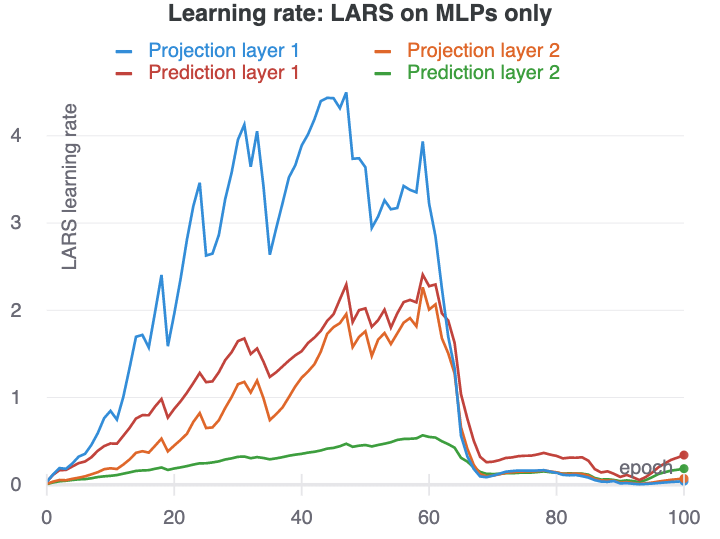

Using LARS on layers 1&2 was most effective at quickly creating separated layers. LARS was somewhat effective at disrupting the training of collapsed representations even if used in just the MLPs. However, in this case the representation usually collapsed again after some time.

The ability for LARS to disrupt learning of collapsed representations appears to strongly depend on the timing of the learning rate changes. For example, with a base learning rate of 0.5, the learning rate in layer1 peaks in epoch 2, and the network starts to learn useful representations immediately after that. With a base learning rate of 0.1, the learning rate peaks in epoch 9, and the network does not recover from the collapsed representation it has learned.

Overall, we find these interactions to be quite fascinating, and consider them to be worthy of a more in-depth study in the future.

For our present purposes, we have shown that the ability of BYOL to learn useful representations with LARS without batch normalization is particular to the adaptive layerwise learning rates of the LARS optimizer rather than a general property of BYOL training.