RSS · Spotify · Apple Podcasts · Pocket Casts

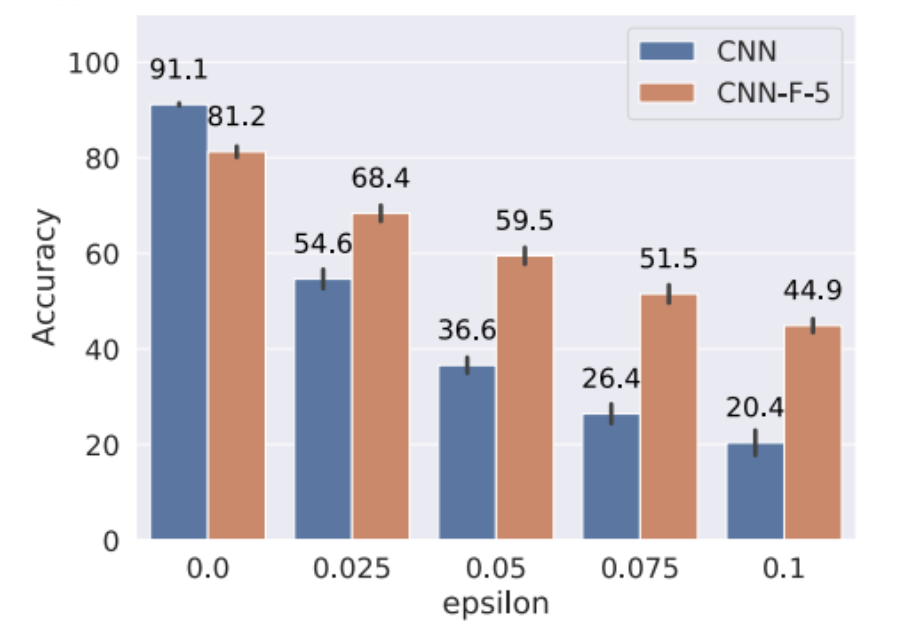

Her most recent paper at NeurIPS is Neural Networks with Recurrent Generative Feedback, introducing Convolutional Neural Networks with Feedback (CNN-F).

Yujia is open to working with collaborators from many areas: neuroscience, signal processing, and control experts — in addition to those interested in generative models for classification. Feel free to reach out to her!

Highlights from our conversation:

🏗 How recurrent generative feedback, a neuro-inspired design, improves adversarial robustness and achieves similar performance with fewer labels

🧠 Drawing inspiration from classical ML & neuroscience for new deep learning models

📊 What a new Turing test for “less artificial” AI could look like

💡 Tips for new machine learning researchers!

Below are the show notes and full transcript. As always, please feel free to reach out with feedback, ideas, and questions!

Some quotes we loved

[04:19] Generative classifiers needing less labels than discriminative ones: “I got very interested in the idea of using generative models to help classification. It’s actually a pretty old idea, dating back to 2002. Andrew Ng published a paper saying generative classifiers actually can learn more efficiently than discriminative classifiers. You can prove that if you learn using a generative classifier, you need less labels than a discriminative classifier. Intuitively, I think it makes sense because you are trying to get a global sense of the data distribution rather than trying to memorize which Y you should map your X to.”

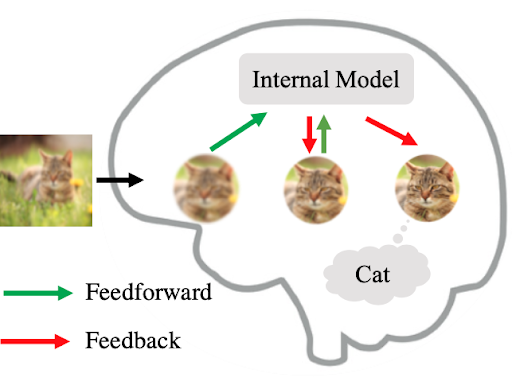

[06:58] Generative models for classification: “Why do we need generative models in our classification? I was thinking, if you see a cat, why do you know it’s a cat? It’s because you have the image of a cat in your mind, and you match the external input to the impression or the memory you have in your mind. The memory you have in your mind, or the picture of the cat in your mind could be the result of a generative model. I was thinking of using this sort of generative modeling and this is what I call a recurrent generative feedback in my paper, that could help robustness.”

[28:06] Inspiration from neuroscience and crosstalk between fields: “I think that people can get inspiration from neuroscience. Look at some classical neuroscience facts or findings, and then formulate it in the language of machine learning to see whether we can get better guarantees using some theoretical tools. And of course, run some experiments to see whether it works or not. After you have this machine learning model, maybe neuroscientists will also take that model to see whether that can provide a better model for neuroscience.”

[30:44] A Turing Test for deep learning models: “We probably need to have a test for deep learning models, something like a Turing test for deep learning models. One aspect of that test might be the brain score. There could be a lot of other tasks that people can think about.”

[39:38] Training models based on attention: “To look at different patches of images (during training) - I think that’s very biologically plausible because we do scanning over the visual input ourselves. That attention mechanism is not controversial to what I have developed and these can be combined.”

[54:29] Advice for new researchers - read classical literature: “I realized people who are very successful in research always find classical stuff and make use of that. I have friends who work on optimization and they proved some theories in stochastic mirror descent and the tools they were using were actually from control theory. That paper dates back to the 1960s or 70s. Try to constantly look back and think, how can I use those tools in my research?”

[56:41] Advice to new researchers - discuss with others: “It turns out for a lot of ideas, the bingo moment was from discussion with others. It’s faster to learn things via talking with others because they already processed all the data and they are explaining it to you after they’ve seen 20 papers in the same field. For young grad students or researchers, we should have the courage to discuss with people.”

Show Notes

- Yujia on how she came up with her idea for Recurrent Generative Feedback for CNNs [00:00]

- Intro [00:46]

- Yujia’s path to machine learning [1:46]

- Exploring open research problems in school [4:08]

- Generative models for classification [6:58]

- How CNN-Fs and recurrent generative feedback improved upon robustness [8:09]

- Different types of robustness [8:25]

- Anil Seth’s work on consciousness and hallucinations [12:11]

- The origin (theories and previous research) of how Yujia came up with her most recent model [13:55]

- Yujia’s main neuroscience and cognitive science inspirations (James DiCarlo, Josh Tenenbaum, and more) [15:54]

- Biologically plausible generative feedback mechanisms [21:54]

- E-prop vs backprop [22:24]

- How can we properly take inspiration from neuroscience? [22:57]

- How neuroscience and artificial intelligence learn from each other [26:08]

- How does Yujia define “less artificial” artificial intelligence? [29:17]

- A new type of turing test for AI [30:43]

- Making neural networks more intelligent [33:34]

- Disentanglement to help with robustness [34:33]

- Making neural networks smarter during testing [37:19]

- Other inspirations: predictive coding and classical research [41:23]

- Generative models in human brains [47:13]

- CNN-Fs and why they need less labels [48:39]

- Concepts in cognitive science [50:25]

- Recurrent and generative feedback in humans and cognitive science experiments [50:59]

- Tips and tricks for new machine learning researchers [54:14]

- The collaborators Yujia would like to work with [1:02:45]

Transcript

Yujia Huang: So I was thinking, imagine you see some blurry thing, it’s a cat. So if you see some blurry thing, you will have some guess, its probably a cat, but how can you verify whether that’s a cat or not? What would be the thinking process? So you generate something from the label of a cat in your mind and you try to match the generated image with the external input.

Yujia Huang: If these two match with each other, then bingo you got the right category. The memory you have in your mind or the picture of the cat in your mind could be the result of a generative model. I was thinking maybe using this sort of generative modeling and what I call a recurrent generative feedback, that can help robustness. Then I develop this idea into the paper.

Kanjun Qiu: Hey, everyone, I’m Kanjun Qiu, and this is Josh Albrecht. We run Untitled AI, an independent research lab, that’s investigating the fundamentals of learning across both humans and machines in order to create more general machine intelligence. And this is Generally Intelligent, a series of conversations with deep learning researchers about their behind the scenes ideas, opinions, and intuitions that they normally wouldn’t have the space to share in a typical paper or talk. We made this podcast for other researchers.

Kanjun Qiu: We hope this ultimately becomes a sort of global colloquium where we can get inspiration from each other, and where guest speakers are available to everyone, not just people inside their own lab. Yujia Huang is doing her PhD at Caltech. Her research interests lie at the intersection of deep learning and neuroscience.

Kanjun Qiu: And her hope is to design less artificial intelligence. She’s currently working on neural inspired generative models to move toward this goal. I’d love to start with, how did you develop your initial research interests? I know you have a pretty unusual background. You were in biophotonics before you entered machine learning, so what happened? How’d you get started and how did your interest evolve?

Yujia Huang: I think compared to other grad students in machine learning, maybe I did have much more unusual path. So when I was in my undergrad, actually I did an undergrad in electrical engineering, but in our school we have more detailed branches. So I chose to learn optics and biophotonics at that time because I really liked physics, and I wanted to do some experiments to verify my ideas.

Yujia Huang: So it turns out that in deep learning actually, the procedure might be similar, so you know as some physics principle and some math principle, and you want to design some architecture in deep learning or algorithm to verify whether that works or not. What I’ve chosen is for physics and some experiments with stuff. And then also when I applied for grad school, I applied to the same direction while, I entered Caltech, our school provided a lot of freedom for the students to choose courses. So I ended up taking a lot of courses in electrical engineering which is the department I’m in, but also in computational mathematical science department, which is a big department to contain computer scientists, applied mathematicians and control experts. We apply those methods in some of the computational imaging aspects in biophotonics research, but the main powerful biophotonics research is you have to build optical systems, so it’s more of the applied physics things. I really wanted to apply the things I learned from those math courses to my research. So I generally developed more interests in deep learning. And then I also took courses in deep learning and we would need to do some course project for that.

Yujia Huang: So that’s how I got started doing research in machine learning, because it’s very different in whether you are taking a course and we would do research. There are sometime you need to apply what you learning and to think about what are the open problems, because all the things that are taught in the class, I already solved problems, otherwise it wouldn’t be in a textbook. I started doing research through that course project yeah, later on, I just feel, “Yeah, why not just becoming a machine learner?” So now machine learning has become my main research.

Kanjun Qiu: Interesting. What did you discover about the open problems as you were exploring after taking these classes?

Yujia Huang: There are a lot of projects idea provided by others, and I took a look at them and then I got very interested in the idea of using generative models to help classification. It’s actually a pretty old idea, maybe dates back to 2002, Andrew Ng published paper saying, “Generative classifiers actually can learn more efficiently than discriminative classifiers.” At that time he was using a very basic model, Bayesian Naïve, Bayes model and logistic regression.

Yujia Huang: So those two models are discriminative and generative pair. You can prove that if you learn using generative classifier, you need less labels than discriminative classifier. And intuitively I think it makes sense because you try to get a global sense of the data distribution rather than trying to memorize why you should map your X to the idea of generative modeling is intriguing because I kind of want to grasp a lot of knowledge of all the data which we might be lacking if we directly memorizing from mapping from X to Y.

Yujia Huang: So I got interested in that, but how to use generative model to help classification. That’s not easy because you can learn it more efficiently, but asymptotic error for generative classifier will be a little bit higher than discriminative classifier. Meaning that if you learn long enough, you might end up slightly worse, although you need less labels. On the website for example, we can get enough on supervised data without labor, but it’s still from Gaussian Naïve model to resonates, there’s still a very big gap.

Yujia Huang: It’s challenging to give any of theoretical guarantee if we use a generative classifier, at the same parametric form of resonate or something that, would we have better performance. If we do have better performance in what way do we save some labels or do we have other good properties? So I’ve been thinking about that. And at that time when I was reading the project ideas from the course, there are the paper called Neural Ranger Model at that time.

Yujia Huang: So that paper basically trying to derive a generative classifier who had the same parametric form as CNN, convolutional neural networks. And so that’s pushing the generative classifier from Gaussian Naïve model or back at the days when ASPM was popular to learning models. So this is the basic model that I started with. In the original paper, they did some semi-supervised learning experiments and they find, “Okay. Using their generative classifier, there are some performance improvement in semi supervised learning,” which is the same task that Andrew Ng was doing, using less labels to learn.

Yujia Huang: So the generative power is different. Why we need generative model in our classification. So I was thinking if you see a cat, okay, it’s a cat. Why do you know it’s a cat? Is because you have the image of a cat in your mind and you match the external input to the impression or the memory you have in your mind. The memory you have in your mind, or the picture of the cat in your mind could be the result of a generative model.

Yujia Huang: So you generate something from the label of a cat in your mind, and then you have some image, and now you compare with some external input. Imagine you see some blurry thing and that’s a figure Y in my paper. So if you see some blurry thing, you will have some guess in the first, is probably a cat, but how can you verify whether that’s a cat or not? What would be the thinking process? I think one hypothesis is that it could be, you’re trying to generate something. Then you would try to match the generated image with the external input. If these two match with each other, then bingo, you got the right category.

Yujia Huang: So I was thinking maybe using this sort of generative modeling and this, what I call a recurrent generative feedback in my paper, that could help robustness. Then I develop this idea into the paper, where I incorporate recurrent generative feedback into CNNs and apply it to some adversarial robustness tasks to see whether that helps this robustness.

Kanjun Qiu: And it seems to help quite a lot.

Yujia Huang: Robustness is actually a very big field in deep learning, even adversarial vastness. I think the most established way I think works practically is adversarial training, trying to do a min-max optimization, you try to minimize the loss under the adversary, but then later on, people do a certified adversarial robustness, and make sure that within some Ip norm ball, if you make perturbation within that ball, you can make sure that the network’s output doesn’t drift far away.

Yujia Huang: Typically, for certified robustness, the Ip ball is very small, which is hard to make it to be a very useful practically, but I think it’s actually very interesting as a theoretical problem. There is always a gap between theoretical and practical, and what works practically and what people understand theoretically, but I think it’s important to go from both ends. So that’s for our adversarial robustness.

Yujia Huang: And also currently we have a lot of other, what people call corruption robustness, where we don’t have as malicious perturbations as in adversarial attack, but we have larger perturbations, still, rainy or Gaussian noise, shot noise, all those are corruption. So people also now have a corrupted benchmark on that. So in the NeurIPS Paper, I was doing adversarial robustness, but I’m also exploring whether this feedback mechanism can provide us some unified robustness. That’s why I now concentrate on the word adversarial robustness, because there are all types of robustness.

Kanjun Qiu: Ah, interesting.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah.

Kanjun Qiu: Okay. Aside from corruption robustness, what are some of the other types of robustness that you’re interested in exploring?

Yujia Huang: The two main category that has been trending is now adversarial and corruption. And actually corruption, I feel it’s much harder to model it mathematically or rigorously because people have some models who generating those data with snow, or with some digital, or all sorts of effects you can have, but it’s hard to really formulate it. As far as certified robustness for example, you can formulate the perturbations within the NLP ball. But in general, it’s just very hard to measure the perturbations in high dimensional space, the image space.

Yujia Huang: So one of my colleagues actually, at Caltech, he did a very interesting toy example. He chose three different images and compute the L2 norm of the difference pair-wisely between these three images. And if he asked a human to tell, which two images are closer to each other? And then he will show you actually the L2 norm between the difference of these two images is the largest.

Yujia Huang: So that shows actually the L2 norm is not a very good way to measure the distance between images, right? Although naturally we use L2 distance to measure how far away are two people, for example physically, but it’s not a very good metric image space, and that’s why again, or some generators people use these adversarial law. So they use a neural network to learn the distance between images.

Yujia Huang: So I think that’s still an open problem because I think now we have not very good, but still we have some understanding of certified robustness under L people. But what about these unified robustness where we could have all sorts of corruption, maybe following some physics process that because snow or rainy or those effects could follow some procedure to generate, we might not have a very good mathematical way to really formulate that.

Kanjun Qiu: Interesting.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah. Exactly how hard is rain versus snow versus fog versus white noise versus it’s really hard for us to talk about those things image space.

Kanjun Qiu: It’s also really hard for me to think about it as a human. Actually, one thing I want to mention that was really interesting about your approach is, I’ve read a lot of Anil Seth’s work, Anil Neil Seth is a neuroscientist, and he actually gives this Ted Talk, which you should definitely watch if you’re interested in this, called your brain hallucinates your conscious reality.

Kanjun Qiu: So in theory, his neuroscience work is on consciousness, but actually what he talks about in this Ted Talk and a lot of the papers that he cites, has to do with this idea that your brain is not just taking in external input in order to figure out what’s going on. Your brain is actually constantly making internal predictions, images of what’s going on. And those predictions feed into your model of your determination, your clarification of what’s going on, just as much as the external sensory inputs.

Kanjun Qiu: An example he gives is very interesting is, he played a noise and it sounded like noise to me, he played a few times, I could not recognize the noise. Then he plays a person saying, “Brexit is a terrible idea.” Then he plays the noise again, and I can hear in the noise, “Brexit is a terrible idea.” It was just a noisy version of what he was saying. What that goes to say is, okay, when my brain has hallucinated what’s going to happen. Then that actually changes the way I perceive incoming things. And this is what your work reminded me of is, actually what you’re doing is you’re producing a hallucination internally.

Kanjun Qiu: The whole line of work of using generative models for classification reminds me of this, but yours in particular, this diagram in figure one, I actually wanted to ask, sounds like this is something actually you just came up with that based on observing what’s going on in your head, Have you looked at any of the neuroscience behind it and I can send you these papers?

Yujia Huang: Yeah. That Ted Talk, I will definitely check it out. As for my idea. So at first I came up with this idea of, if you got one of the cat idea, first myself about this doll experiments. And I did look into a little bit into the neuroscience paper. It’s also very similar experience to predictive coding, that I also mentioned in the paper. So it’s actually a very classical neuroscience paper backed in 1999.

Yujia Huang: It was proposed to explain something called a suppression effect, I think they use monkey to do experiments of stimulus. And if you enlarge the size of stimulus, instead of observing increasing neuron response, you see a decrease in the neuron response, which is contrary intuitively, because if I use a bar as the stimulus, I show a longer bar, at least I think that the response shouldn’t decrease, but they observed that the neuron response decreased.

Yujia Huang: So they tried to provide a model to explain that phenomena. By predictive coding model, they were hypothesizing that actually the forward signals are not the actual signal, but the residual errors of the predicted signal and the actual input. And that’s why if you see some bars for instance, you probably have some models in your brain, you have a guess of what you will be saying, and then later on another input.

Yujia Huang: And that kind of matches with what you have in your brain, then the neuron responsible decrease, because there is zero errors of your prediction and what you actually see is small. So that’s also a similar spirit as the Ted talk and also my paper. Our brain it’s being actively thinking about what’s going to happen. If things happen in the same way, then the surprise will be low or the residual errors, or the neuron responsible will be low. Predict coding is in the paper that really assure me that, okay, my thought experiments might have some neuroscience groundings.

Josh Albrecht: Are there other sort of ideas either thought experiments or from biology that you found inspiring or similar ideas that you wanted to do research on?

Yujia Huang: So neuroscience is a very big field. There was a conference in November, we’ll have over maybe 30 or 40K people attending it. Yeah. I don’t have a neuroscience background, so most paper I was reading might be on a kind of, I read a high level end idea, maybe the methodology part of the model if it’s a computational neuroscience paper like predictive coding. And I try to see whether we formulated in deep learning about that paper that I read.

Yujia Huang: The most neuroscience papers I was reading are from James DiCarlo or Josh Tenenbaum from MIT, where I think a paper by James DiCarlo, they observe that the object solution time is longer for challenging images compared to normal images. So they have two data sets. One, is the control set, which contains some clean images, and the other one is the challenging set where the object might have blurriness or occlusion on it.

Yujia Huang: And it turns out that the monkeys takes longer time to recognize the object in the challenge set compared to the original set. That paper was talking about actually the adversarial samples generated in neural network, and also for human beings. Within a limit period of time, they said in the paper, for example the original image is a snake, but they clear neural network and they generated adversarial sample to fool the neural network to believe that image is a spider.

Yujia Huang: And then they showed the adversarial image to human beings where they have very short period of time, quite amount of participants gives the wrong prediction. Maybe you have to program something to show it to be really sure. Because I was reading a paper, I can look at the picture for quite a long time, so I know that what it is. So all these paper actually suggest that there might be something going on in the brain when we’re dealing with this shift, but what’s actually happening, I guess nobody really knows.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah.

Kanjun Qiu: Yeah. Hearing that, the thing that comes to mind is what might explain a human being fooled in a small time span, but not being fooled when you look at for a long time, maybe some lizard brain reaction is happening in this small time span, and no reasoning is going on. So we’re not using our prefrontal cortex or other parts of our brain. And so other parts of our brain are patching up our understanding by adding context and adding other things, but the lizard brain got fooled.

Josh Albrecht: There’s probably, I think lots of different mechanisms, this is probably why this happened. So one is we’ll talk feedback, which is kind of the paper, that sort of idea, but there’s also, it doesn’t necessarily need to be talked out with feedback or there could be other mechanisms where you paying attention. So you’ve looked at this one point, but maybe you look somewhere else in the picture, so now you have the more information that you can take in, but even as you process, if you just are staring at the same thing for a little while, even though not very long hundreds of milliseconds, and you will still continue getting extra information versus seeing it just for 10 millisecond or something, super small.

Josh Albrecht: So there’s many different things happening. And then there’s this top-down signal again, I think as you pointed out Kanjun come from reasoning. “Oh, they told me it’s supposed to be a picture of a snake so I guess it’s a picture of a snake.” Okay. I think we all slow. And then there’s probably other lower level versions of that as well.

Kanjun Qiu: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah.

Josh Albrecht: Or like, “Oh, I just saw some of this or this are some of the findings examples.”

Kanjun Qiu: Right. Basically, some of priming examples don’t replicate, it depends on how you define priming. If I first heard this example about Brexit, the phrase I used earlier, if I first hear that, and then I hear the noised up version of it versus if I only hear the noise up version of it, of course I would expect that I would know what the noise up version is if I first heard it. Maybe what’s going on there as I’m feeling some kind of prediction internally, based on my previous state and having been told what this is about.

Yujia Huang: I think there’s a very interesting book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. There’s system one and system two argument. And in that book, the author gave a lot of example about for each system one and system two lot of example. And priming in fact was one of them.

Josh Albrecht: And I think there’s also a whole class of optical illusion almost, but it’s not just optical, there’s also audio versions of this, where you can look at a picture and see one thing, and then you can consciously decide to see the other reverse image.

Yujia Huang: Like the face versus the vase thing. My model or similar models that use are using generative model can also help explain the face versus vase thing. So basically you should have some bi-modal distribution in the end, right? Sometimes you think is a face sometimes you think it’s a vase. So if we think it as a classification problem, we probably for Y, sometimes we’ll have one zero, sometimes you will have zero one. And for these two, maybe what you are focusing on is kind of different.

Yujia Huang: So you might think you know the contour pointing inwards, that might be the face part, if you think that way, that will give you a face. But if you think of the edges that pointing, that will give you the other object. So if you have a generative model, maybe you go to one zero, and you generate something, that should give you the right direction of thinking and then, okay, it matches what, but for some reason, maybe some stochasticity is you just jumped between these two states.

Yujia Huang: I don’t have that in my model, but I think that’s a very interesting thing to look at is how to add randomness or stochasticity to the model, because you might jump between different states.

Josh Albrecht: Is there no randomness in the current one? I thought that where exactly do the initial Zs and MAP come from?

Yujia Huang: Zs are initialized by CNNs.

Josh Albrecht: Oh, by CNNs.

Yujia Huang: So basically I’m doing MAP estimate, maximum a posterior estimates, which is some point estimates. I did not add a randomness in it. So if you add randomness, it will help your model, the distribution better, but it will also make training harder. People argue is that bad propagation is not really biological plausible because we don’t want to have loss function in our brain for us to back again.

Yujia Huang: And we wouldn’t know the way, it’s maybe globally because we need all the way, it’s an activations when we do that backprop. In general, it’s hard to see some, we target propagation or some other biological plausible optimization methods to really beat backprop at the moment. Although I think we should keep studying that, I’m not saying that it’s not important, but it’s hard to scale up.

Kanjun Qiu: Actually. I think Josh has a controversial opinion on this.

Josh Albrecht: I do.

Kanjun Qiu: Yeah. The controversial opinion is we know backprop is not biologically plausible, however, maybe the optimizer doesn’t matter that much. As long as you get to the optimum, the type of optimizer doesn’t matter. And it seems to me that backprop is way more efficient than any biologically plausible optimizer. It’s possible that we actually have a better optimizer than our brain does maybe, and we’re still able to get to the same place.

Yujia Huang: Yeah. I mean, that’s also a debate, right? I’ve been thinking about how to properly conduct research that take inspirations from neuroscience. If I talked to some theorists or mathematicians they will be like, “Yeah. I know this is more biological plausible, but does it make sense in terms of mathematics or can you prove to me this really will work, right?” That’s the same thing. Okay. You say bad propagation is not biological plausible, you provide something as more biological plausible.

Yujia Huang: But in terms of optimization, maybe that cannot be better than that backprop. So in terms of the planning, maybe we should use the one that can be proved in terms of math or theory, that’s going to give us better performance. So how to really take good things from neuroscience, I think that’s something that’s worth thinking. Should we learn everything from human? Is human brain necessarily the truly intelligence that we want to learn?

Yujia Huang: Of course it would be great if we can build something a brain, but that’s just a truly enormous project. Maybe after 100 years, we will say, “Ah, maybe a backprop indeed like some the biological part.” But sometimes if we just see some partial biological inspirations that might not necessarily outperform the existing tools. So I totally agree that. And I think that’s also something that we should keep in mind when we do these neural inspired work in deep learning.

Josh Albrecht: There’s something that’s very interesting to me. One on the backprop specifically, there was interesting work last year I think, called e-prop A friend of mine was very excited about it because it supposedly is not as good as normal back propagation, actually when they showed that you can make these kind of traces and then the traces were much, much more biologically plausible and you could find a really good analog to that. It’s like, “Oh, okay. Actually, this algorithm is not quite as good as backdrop, but it’s almost as good, and it’s almost completely biologically plausible.”

Josh Albrecht: So maybe the brain really is doing something interesting there, I know it’s off by 10% or whatever, but it doesn’t need to be perfect. It’s good enough for us to learn and make sure we don’t step on snakes. For me what that does, as we find out more about the brain, I think we’ll keep uncovering more things, “Ah, I see what it was doing, that’s actually pretty clever.” I mean, in some cases it might be more clever than what we’re doing, in other cases, not quite as good as what we figured out doing that.

Josh Albrecht: I do think it’s really interesting to see ideas go back and forth between these two fields. And I always love seeing things that are biologically inspired, because it’s really hard to tell ahead of time, is this going to be one of those that’s really helpful and actually moves things forward, we really should have thought of that. Because we’re competing with evolution as ML researchers, I think we’re pretty smart, right? Were generally intelligent, but evolution ahead a long time.

Yujia Huang: Exactly.

Kanjun Qiu: I think another thing that’s interesting about intelligence is that we could say that it has actually evolved multiple times. So octopus are intelligent in some sense, crows are intelligent in some sense, dolphins are intelligent in some sense. They’re not human level in some important way, but certainly they have planning and communication and all of these other things. Taking only inspiration from human brains is not necessarily the best way to go. So that contributes to the question of how do we take biological inspiration. Do you have any answers?

Josh Albrecht: You should use theory or biology, or tell us the answers?

Yujia Huang: Oh yeah. I don’t know the answer, but I do agree with what Josh just said that, I’d like to see the two field interact and help with each other in turn. Yeah. Theory and practice, right? Sometimes we do experiments for us to find some interesting phenomena using theory to explain that, sometimes the other way. Even for neural networks, right? But for us, we are maybe in the first, I’m not sure whether hinting God’s inspiration from neurons or who came up with the idea first.

Yujia Huang: But I think I heard Yann Lecun when he was talking about convolutional neural networks, maybe they did take some inspiration from a receptive field or visual cortex processing the images. But after that, people do a lot of engineering or mathematical efforts in deep learning to really try to give guarantees or try to really make things work. There are so many non-neuroscience, deep learning papers coming out. A lot of times I will feel, “Oh, what should I be working on?”

Yujia Huang: Because all the ideas have been working on by some other people. What should I be working on? And there will be actually the space to explore is huge. You can go into one direction. There is a lot of work and you can make improvements upon that and could be an idea, but the searching space is too large. So sometimes if you can find something in neuroscience or cognitive science, that has had been verified by some experiments, or that’s in classic, or that’s all known facts, maybe, or I’m not sure there is actual fact in neuroscience.

Yujia Huang: I’m talking about maybe some effects or priming fact or something that we know, and take those inspirations and to formulate something in terms of using the mathematical tools. And hopefully we can also provide some more theory guarantees on that. Although currently, I don’t have theoretical guarantees for my paper, but I was thinking this is basically introduced some dynamical process to neural networks.

Yujia Huang: And whether we can use some tools from a dynamical essence to show actually doing this sort of feedback can help us get better robustness. I think that people can get inspiration from neurosciences. Yeah. Look at some classical neuroscience facts or findings and then formulated more rigorously or in the language of machine learning, and then see whether we can get better guarantees using some theoretical tools, and of course, running some experiments to see whether it works or not.

Yujia Huang: After you have this machine learning model, maybe neuroscientists will also take that model to see whether that can provide a better model for neuroscience. So same thing for convolution on that. So in the first place, maybe comm. nets was inspired by neuroscience. I think neuroscientist studying visual perception, they use cognitive like a tool to predict neuronal response, it goes back to model in neuroscience.

Kanjun Qiu: That’s right. It’s kind of we’re accidentally developing a field for modeling our brains.

Yujia Huang: Yeah. You can use it either way. For my model I hope on the one hand, I hope it can help with the robustness, and on the other hand, I hope to maybe compare with some neuroscience data to show whether these sort of feedback can gives us better data.

Kanjun Qiu: One thing that you mentioned on your website that I wanted to ask about actually is that, you said your research is at the intersection of deep learning and neuroscience and your goal is to design less artificial intelligence. I think the term was really interesting. What do you mean by less artificial?

Yujia Huang: I want to reduce the gap between human intelligence and artificial intelligence. So artificial, this word sounds like restriction or less the power generalization. I think that’s kind of another way to put AGI, artificial generalizable intelligence. Also, by less artificial, less some like more rigorous definition.

Yujia Huang: When people say we want artificial intelligence to be more human, what are we really saying? I don’t think we have very good regular definition or regularization in the field at the moment. People are making progress multiple ways. I know a data set called brain score, which also, I think proposed by James DiCarlo’s Lab. Nowadays they have a leaderboard and people will submit their model and see whether a model can predict a better brain score.

Yujia Huang: I think that benchmark is of course helpful, but still we might want to ask more in depth, what does it mean if we have better brain score? Does that really mean that it looks more like brain? It’s something that we need to think about?

Kanjun Qiu: What do you think? How would you define less artificial? More human, along what axis?

Yujia Huang: I think predicting neural response is something that we can try, but the thing is we probably need to have a test for deep learning models, something like Turing test for deep learning models. And while aspects of that test might be the brain score. And there could be a lot of other tasks that people can think about, right? In my lab, there was another researcher propose some tests called Bongard game, something that IQ it has to see.

Yujia Huang: So you’ll have something like shapes. And you need to find which shape doesn’t look like the other. For example, you have a bunch of convex shapes, but inside it there is a concave shape, you need to be able to tell the pattern. So something that could be a test, that’s how you will reason about a visual input. Some other tasks could be, if you see two images, like maybe in the brain, it’s not really processing the data classification or regression.

Yujia Huang: If you see llama or something, you cut it off and maybe there will be some cattle in it. It might look a smiley face, but in green. Whether that’s a llama or a face. So in our brain we have these two aspects. So why these self supervised training works really well, it’s actually learning the distance of images in a way that is more similar to how we think, it’s not only that they have the same label, because label contains really high level information. But we should be really looking at the compositionality of the images.

Yujia Huang: What are the critical components in the image that has the perfect meaning. So all of these tasks, reasoning task, and some tasks to judge, whether the similarity or difference between images or whether it’s more similar to neuronal responses, all of these, I think are the tasks that we can use to evaluate whether the model is more human. To better or maybe regularize is people need to brainstorm about what tasks we should be using, because the only way we do this is we need to probe it, probe the model to see whether it’s human brain or not.

Yujia Huang: We cannot go from anywhere because there’s nothing there. So we don’t have an agent or the agent are the artificial agents that we create. We can’t really go into our brain to break every part, to see what are there. So we can only probate it to see whether the reactions from the actual black box spring, which is our brain, human brain and the artificial agents. I was thinking a brainstorm about the tasks that we can use it to better define what we mean by artificial general intelligence, to evaluate how our models on those tasks for now, before we have the power to break up all the parts in the brain.

Kanjun Qiu: Not even thinking about how the field can think about artificial general intelligence, but for you personally, for the work that you’re doing, how do you think about less artificial? How do you define it for yourself?

Yujia Huang: For less artificial, I just feel neural networks are sometimes too stupid to be fooled by the adversarial samples. So it is a cat, but I can fool you to believe it’s a dog. So I was thinking, “Ooo, why is it stupid? So how can I make this to be smarter? So what if I let the network to know what a cat look like?” If the neural network also knows what a cat look like, it wouldn’t be fooled by the dog label. And what if I add the generative model to the network? So from a label of a cat, it will know what I would actually look like.

Yujia Huang: So if your label is a dog, you generate some image that will look a dog, and you will know something is wrong, right? Because the image of a dog doesn’t look what the image that I’m actually seeing. So that’s some idea that I had in the first place in my mind is that I need to add something more to the neural network, so that at least they will have more smarter or more intelligence. The neural intelligence in my model comes from this generative part.

Josh Albrecht: That idea is really interesting. I think a lot of it came down to these consistency losses or the label and the input to be consistent. I’ve always wondered that, or maybe you have some thoughts on this, how far can you take this idea? If you take this and just push on it and say, “That needs to be consistent with the label, true. That needs to be going to generate a consistent image.��” But also when I’m looking at a picture, there’s lots of other constraints, there’s lots of other things that are consistent.

Josh Albrecht: There was a previous image I saw? What kinds of memories have ever seen in the past? What does the other edge of that image look like? There’s lots of other things you can maybe connect it to, and I was wondering if you had any ideas what else could you include in this consistency loss such that you can make it even more robust?

Yujia Huang: Currently in the model, we don’t really do disentangling of the component image. This disentanglement, I think it will help a lot. For example, a generated image from the label shouldn’t match exactly with the input, right? Because the input image is noisy, but if it’s raining outside, I would know what I should expect from raining. That means I can’t decompose or disentangle the noisy part and actual the image part.

Yujia Huang: Literally we can do things for foreground and background, right? But for the label, we have the label of a cat and the background we can have grass, and now I can make better consistence loss between the corresponding parts in the image. I think that would be quite helpful in the model, but currently I didn’t do any decomposition or disentangling, but I think that’s something that really interesting and worth further investigation.

Kanjun Qiu: Interesting.

Josh Albrecht: I can imagine disentangling a channel for depth. So you had mentioned segmentation or temporal things like this is a video and so the image should be hopefully a lot easier to make all of these things consistent, it doesn’t flip from dog to cat and very rapidly from frame to frame, that kind of thing can help a lot, and the depths would help a lot. I wonder how far that goes.

Yujia Huang: You mentioned in the very beginning of this conversation, this message works better if we have more information as inputs. And because we are tying to reasoning about things. If you just have one input, it’s just hard for you to make any affirmative decision. So you always want to collect the data. So that’s also something that I think if we can design something to let a agent to actively collect data, and that will be interesting to first, you have some expectation, and then probably you will also have a better idea where to collect the data.

Yujia Huang: I guess, as Josh mentioned, we probably already have some data say like a video on a self-driving car, because this thing doesn’t change very rapidly. So you have some very continuous flow, but you want a little bit of new information coming in continuously. And to make use of those information, I think will also be a very interesting future work. I saw some test time training paper, where people used them, auxiliary task. Tests and time is just, we don’t really have the ground truth label, but we probably have another auxiliary task for us to make our decision. I think they use one of the standard protect tasks, self supervised learning, which is they rotate the image.

Yujia Huang: So they’ll keep the main part of the neuro network, but add another branch to do this rotation prediction task. And during testing time, they optimize over this task because they know what rotation do they rotate this input image. And so they will update also the parameters in the main branch. And that will also help with the classification task. Also during testing time, if we can use this consistency loss or these consistent constraint, that’s also something as an auxiliary tasks, we want the perception to be consistent.

Yujia Huang: So from the label to the image, and maybe between the video frames, if we use that, we can also be smarter during testing time. In my work, what I mean by less artificial is that we can be smarter during tests now, because previously in neural networks are trained, it’s done, right? In testing time you do whatever to it. It doesn’t have any power to fight back. Now I want neural network to be able to fight back during testing time. If you try to fool it no, you cannot do that.

Josh Albrecht: Another idea actually, building on that. As you were saying, we want the network to be able to go collect new information. Another thing I’ve been thinking about is can you do a sort of hard attention or foviated attention type thing where the new information being collected, it was already there, but instead of you taking everything all at once, maybe have a high resolution photo, maybe you can actually figure out, probably like, okay.

Josh Albrecht: But then if you know the label, you should be able to say, “You know what” If I look at this particular really small patch, it should look this, and I look over here, it should look this, if I look over here…” It’s going to be really hard to make an adversarial thing that can fool you. I think my intuition is, it’ll be a lot harder to fool that because now you can choose any kind of subset anywhere.

Josh Albrecht: If you get to choose anything anywhere as the network, it’s going to be really hard to tweak each of those little things, they’re going to push you in the wrong direction. What are your thoughts on maybe incorporating attention as a way of also allowing it to collect more information?

Yujia Huang: I think people have been doing work. What you just mentioned to look at different patches of images. I think that’s very biological plausible because we do scanning over the visual input. That attention mechanism is not controversial to what I have developed, at least it’ll be combined.

Josh Albrecht: That’s what I was thinking. It seems sort of natural. There have been other people doing interesting work. I think we’re going to talk…

Yujia Huang: Right. And that also related to some disentangling part, because when I focus on backgrounds, I extract the information of the background, of the foregrounds, I look at the cat, but the background can be very big, and I closer into those. This is related to compositionality. I can create images from a lot of concepts like grass and cat, these are two concepts. Image itself doesn’t have any more important part or less important part itself because it’s an image. So maybe everything is equally important, but depends on the task.

Yujia Huang: Maybe the important thing will shift. If you want to do object recognition, you want to focus on the foregrounds, but what if you, I just want to relax a bit, just look at something green to relax my eyes. Maybe I just want to look at the backgrounds on the grass. So it depends on the task, you should focus on different things.

Yujia Huang: I think the feedback might also help us to try to disentangle those because the cat should be consistent with the label cat, and the background will be consistent with some latent variables, the grass, or if we add more categories. And then we can refine it, we can choose which part to pay attention to based on our task. Combining with attention mechanism is definitely a very promising direction.

Kanjun Qiu: Interesting extension. Are there any other pieces of work that you feel like have impacted you a lot or you’ve spent a lot of time digesting that work?

Yujia Huang: In terms of this work predictive coding definitely impacted me a lot. There some lessons I learned from doing research. We need to pay attention to these old classic papers. Sometimes good ideas comes from those papers. You need to read machine learning papers of course, to learn what problems we want to solve, but where would the answers lie? Because there are 2000 papers in NeurIPS per year, and we have NeurlPS ICML, ICLR, and we cannot read all of those.

Yujia Huang: The answers might be written in some old book, that is very general, but we just need to adapt it to deep learning models. A variational autoencoder, the idea is very elegant, how we should do inference for a generous model. And that’s actually also very related to the generative classifier, where in generative classifier, you have the same parametric form and in generative classifier, they are not trying to directly learn inference from a generative classifier.

Yujia Huang: They find different training perspective, different losses. But if variational encoder basically this amortized inference, this variational formulation, I feel that’s a very smart idea to encoder or to match the posteriori estimates to the posteriori estimate. And later on, also another colleague of mine from Caltech, he had a paper called Amortize Iterative Inference. So if you want to do some posterior inference in generative model, a very direct way, you can do it by optimization, right?

Yujia Huang: It’s just optimization problem. You try to find optimized for log P of Z and X and Y, and you try to maximize this posterior. And variation on color, saw this by adding an encoder, which is just a one shot inference, but this encoder is trained to by a neural network, that means compared to the optimization method, it might not give you the optimal, because you can just try our best to train as best as you can, but still it’s less optimal than the optimizations that amortize either your inference paper.

Yujia Huang: Just try to reduce this inference gaps by learning to learn method. So refines its inference over several steps, but still faster than traditional optimization like gradient based optimization method. This sort of iterative inference actually I think shows why do I need iterative feedback in my paper? I’m also actually trying to inference for latent variables at each layer, and because I have this variables at all layers, I cannot do it one shot, I do it iteratively to refine a layer by layer and maybe do it again.

Yujia Huang: So I think how to perform effective inference in generative model, those inference from generative models, hopefully could benefit us to do some classic task. There are two ways of the model, right? One way you can model the data distribution, the other way you can learn my higher level concepts from the data distribution, and that part inference. And also, I think these recurrent to feedback idea is also connected to the inference in generative models and I’m very interested to look at those holistic model where they develop new infrastructure tools.

Kanjun Qiu: Yeah.

Josh Albrecht: I think there was another paper I thought was related to this. The idea was, autoencoder is actually, what if you put the output of your autoencoder and you fed it back in, it’s the input, when you get this in.

Yujia Huang: Yeah. Exactly. I also saw that paper.

Josh Albrecht: Which really reminded me of yours as well and it’s a very similar thing. Okay, maybe output again and then we feed it back in, and it seem like a very similar sort of thing, I think they found it. In fact, would be easy to not get even anything remotely close to that. And then they fixed that problem and said, “Oh, okay, we get worse reconstructions, but they’re much more robust.”

Yujia Huang: I also saw that paper and I think that paper shows a lot of common variance. So although they didn’t formulate it the same way as we did for self consistency, but I remember they did also try to make sure that if you feed the generated image back to the encoder, again, you should stay at the same point, it should not go away. In my network, I also try to do this iteration after several iterations.

Yujia Huang: If you have a consistent label and consistent input, if these two are consistent with each other, you shouldn’t change your label or the impression your brain, which is the generative image anymore, because you’re already reach a consistent prediction. And they also find that I think their model also is useful too for adversarial robustness as well. At least they shows that we should add these consistency to neural network, and helps with robustness.

Josh Albrecht: And they all seem like relatively easy things to do. And then we get networks that can’t do tricks nearly as easily, which is great.

Yujia Huang: I do want to mention one thing that you use generative model to help discriminative tasks. We might be asking too much because it’s much harder to model a high dimensional distribution like images than just doing image classification problem. Sometimes we might not want to predict all the aspects of the image. So that’s why in my paper, I actually, I choose which layer to add the feedback to. So currently I’m just doing kind of brute force that I try the several layers and some layers does better, typically, that layer is not on the pixel level. So that means it works better if you first encode our images a little bit to the feature space and then do feedback to that layer, on what level we should do feedback graph. Feedback might happening everywhere in the brain, but for different tasks, we might need to add it to a different resolution or different level.

Josh Albrecht: The brain as you look at it, I don’t think there are any feedback connections that go to the retina that implement reconstruction losses in the same way as this, it very purposely encode it into a thing before you get to start asking about these consistency and reconstruction and top-down feedback stuff. It just-

Yujia Huang: Yes, it makes sense. Because if I ask you to draw something, for example I ask you to draw a cat, can you really draw a cat? If you’re not a painter, I guess that cat really gives you a realistic cat. I can only do some cartoon thing. It makes sense that we shouldn’t be trying to recover all the details of the image. We should try to extract some already processed information from that, from it.

Josh Albrecht: You know don’t actually have a very funny task, for people listening or for you, think about when you’re with a bunch of friends, just take a bunch of them and ask, “Okay, everyone here’s a piece of paper, here’s a pencil, draw a bicycle from memory. You can’t look at bikes, you can’t look anything up.” What you’ll find is that people draw really bad bicycle. Sometimes they’re missing seats, sometimes they’re missing handlebars, sometimes they’re missing wheels, it’s just all over. People are really bad at doing this, it doesn’t matter about art. Again, even get the right number of components and this a really amazing-

Yujia Huang: That’s so interesting.

Josh Albrecht: All right.

Yujia Huang: Just so Josh, you did this at a paper club, right?

Josh Albrecht: We did this. My bicycle was not too bad, but some people, theirs were bad.

Yujia Huang: What was yours missing?

Josh Albrecht: I think the seat bar geometry, the way it interacts with the wheel wasn’t 100%, it’s better to do it the other way. Some people are missing like the seat.

Yujia Huang: It was just really interesting because what does that mean though? Clearly my brain is not encoding pixels, it’s including something else, and then expressing some higher level representation.

Josh Albrecht: I actually have one question. You were mentioning the idea that these sort of generative models versus these discriminative models, it’s you can train with fewer labels, I think you said before fewer examples, when you say that, did you mean literally fewer examples or less information? Because I’m looking at reconstruction losses, et cetera. There’s so much information in a reconstruction loss because you have all the values for all the pixels, whereas if you have a single label, this cat or this dog, “Yeah. Okay. There’s only one bit in there.” The number of bits you have in this image is very high. And so I was wondering, did you mean the lower amount of information or just lower number of examples, but each example is contains more information.

Yujia Huang: Less number of labels, same amount of information. In classification you also have these information, but you just didn’t really try to learn about it, or you’re not really trying to make use of it. I guess maybe also that’s why when people draw bicycles, different people, miss different parts, because they’re not really trained to do that, they’re only trained to, okay, that’s a bicycle, I just need to remember. Choose whatever part from the bicycle and to make that part as your feature part for the concept of a bicycle, you can do this classification task. But after this drawing exercise, I guess, then after that, if you ask people to draw a bicycle again, I guess they probably will draw better, at least they will fill the missing part the next time, because now you add the reconstruction loss to them. They learn, “Yeah, oh each part, what should it be if I’m going to draw a bicycle.” So previous you also have the information, right? Tons of bicycles in your life, but you never really paid attention or train yourself to notice every aspects. But now we add this reconstruction loss to learn and now to know what exists there.

Josh Albrecht: Interesting that you saying that. One other work, basically people have very different ideas for concepts. So they will test how associated are these two words? Or what attributes do you associate with this word or whatever. And think of a cluster. If I say, salmon, some people would think of the fish salmon and some people will think of the food salmon, some people will think of the color salmon. And so the same word, means these different things and people would kind of cluster them in very different ways. And they found that the definitions, they vary wildly across people. Related to that and people latched onto one thing from it, good enough, they can recognize it, okay, great. And just sits there as a sort of half form concept for a really long time until you have to pay attention to it and come back to it.

Kanjun Qiu: It’s so interesting. It’s in most of daily life, we are not forced to do reconstruction, but in school for example, we are forced to do reconstruction, solving problems reconstruction loss, and that is actually very effective way to learn.

Yujia Huang: So I think the reconstruction loss, although it’s not system two, but I think it’s at least one level more requirements than system one. In system one, we just need to do some very quick decision or very quick recommendation, but we want to think about it a little bit more, what we would want to learn. We we might want to learn how to draw a bicycle rather than just to recognize, that’s system two, right? You need to do more reasoning, you need to have more mental effort. In terms neural network, you probably need to do more recurrent feedback processing.

Kanjun Qiu: Actually there’s a study about students in schools, where they study basically how much does a student need to be shown examples of a concept if they do problems related to the concept and answer questions versus if they don’t answer questions. And the result is some order of magnitude 10 to 30X, a student needs to see 30X as many examples of the concept, if they do not answer any questions related to the concept. So that’s very similar to this analogy of, huh, generative models enable you to use fewer examples in training, or humans literally use fewer examples when we use generative models.

Yujia Huang: Yeah. That’s a very interesting experiment Kanjun just mentioned.

Kanjun Qiu: I got very into it a few years ago because I was trying to understand how does learning work? Why does it happen? Why do humans learn it this way?

Yujia Huang: Yeah. There’s a lot of similar student teacher model in deep learning, maybe inspired by these cognitive science. Also the deep ensemble network to deal with the robustness issue. They train a bunch of neural networks to take either the winning decision to the majority or some way to average out actual all the neuro-networks. I think all of these are just good examples where people can take some inspirations from how humans are doing.

Yujia Huang: The other day I went out on a hike with a friend near the ocean, and then there was a ship on the ocean, but for some reason she thought that’s a tin can on the ocean because that’s a very small thing on the ocean. How can there be a big can on the ocean? If you look out clearly you see the window and you see the sailing on that, so that should be a ship. She was just stare at it and she was like, “Oh, that’s actually a ship.” So that means if you actually have multiple networks working together, so each of them can provide others some feedback. I can point out to you, which to pay attention to it.

Yujia Huang: Maybe she was missing some critical features for the concept for the ship and I’m pointing out to her. In modern agent system, you can get more information from also other agents rather than the input. That might be more effective because you can have higher level guidance. Otherwise, you can always still look at the image yourself and try to figure that out, but if you have some other agents that can give you correct answer, you can also help discover where you probably have been wrong.

Josh Albrecht: One of the other questions that I always asking people, are there any tips or tricks or hacks or things that you learned as you started doing machine learning research that you found to be very useful or very valuable, or even perhaps for you, things that you’ve taken from other fields and brought over with you that you found to be very helpful?

Yujia Huang: I realized those people who are very successful in research, they always find classical stuff and make use of that. So my suggestion I would say is, do not bury yourself into tons of papers every year, just skim through it and understand the main problem there in machine learning, and then pay enough attention to classical works. There are tons of examples in there.

Yujia Huang: I also have friends who work on optimization and they proved some theories in distance, and the tools that they were using was actually from control theory. So they then treat the training process as the dynamics in a control system, and proved the convergence of the training process. So that paper, I think, dates back to maybe 1960s or ’70s or sometime like that. I’m not saying that all the new papers that are not good, I’m saying try to understand each and every paper in NeurlPS, but try to constantly looking back and the think actively, how can I use those tools into the research?

Yujia Huang: This form also shares a similar spirit than common filter. Although now I don’t have a video and that’s also related to what we’ve just discussed the idea. If we have a video input, how we should add this consistency loss. Actually something common filter is doing because it try to estimate the states at every time step and try to reduce the error. So this is also a very classical thing. The other thing is I feel also maybe related to this one, this cross discipline thinking could help.

Yujia Huang: Deep learning is a very young discipline, but every discipline should have its foundations or have to make a solid root. If you just learn cognates, I guess you cannot really do anything deep learning, right? It will be helpful to draw the lessons from other fields like signal processing or control or neuroscience, all these fields. The common filter example would be learning something, or processing or control, you will maybe recognize this connection and there might be some new ideas. The third one will be discuss with people. I’m not sure whether that’s just me or every young grad student will have this.

Yujia Huang: Sometimes I just feel too shy to talk to others, to share my work because I feel imposter syndrome. It turns out a lot of ideas, just the bingo moments was from the discussion with others. Almost every researcher I’ve talked to are actually very happy and willing to explain their paper in detail to me. As long as you ask meaningful questions, you’re not really asked some random things. They will be very happy to help you understand their work because that’s also a promoter for their work.

Yujia Huang: And they also hope that their work can be helpful to other research. So it’s much faster things via talking with others because they already processed raw data and they’re explaining to you after they’ve seen 20 papers in the same field. For a young grad student or researchers, we should have the courage to discuss with people often and brainstorm about ideas.

Kanjun Qiu: I love that. And really well said. We shouldn’t reprocess all of the raw data if somebody else has already processed it.

Yujia Huang: You are also processing some raw data yourself. So it’s good to exchange, you’re exchanging with others. And that’s how journal club works.

Kanjun Qiu: It’s a raw data exchange. Earlier you were talking a little bit about some of the important open questions that you’ve uncovered in the field. If you were to talk more about that, you said you have lots of questions. What are some of the questions on your mind or that you would want someone else to figure out that you were curious about?

Yujia Huang: We did also see a lot of more detailed open questions, like how to take use of new information, or how to do this… or attention mechanism. On a high level widely, it was related to how we should define this AGI or less artificial intelligence. I want people to really write some article about what task we should evaluate the model on, what we mean by this, that will make people to think more targetedly.

Yujia Huang: This feedback mechanism, I think it’s a quite general principle. You should have feedback in all sorts of tasks, vision, or an LP or audio processing, all these tasks, but for different tasks, you should design it differently. Without knowing the task, I think it’s hard to do any real thing. So you can just say some big words like feedback, but how to design that might depend on really what task you are doing?

Yujia Huang: So I think the first thing to do is to really better define the goal in a field, when neuroscience meets AI, what are we really want to achieve? I said some examples, whether we can predict the neuronal response, and whether we can do reasoning, whether we can creatively generate things using compositionality, we should better regularize those fields. I think that’s the biggest open problem that’s currently lacking in the field. After we have that, we know what to go for. Then we can use either across discipline knowledge or find a chapter from the old literature to find better tools to solve those problems.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah.

Kanjun Qiu: Yeah. That as the open question really resonates.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah. We wouldn’t be too. Yeah. The most important thing is are we asking the right question? I think a lot more work needs to be done on the problem side machine learning, instead of the solution side. There’s so much good stuff from old literature, there’s so much stuff out there and really, we need to make sure we’re asking the right questions and solving the right problems. I’d love to see more people work on that, strongly agree.

Yujia Huang: I talk with people, I study generative models. It turns out that we are both trying to make use of generative models, but people could focus on very different goals. If you ask people working on a generative adversarial network, most of them will be focusing on generative high fidelity images. They really want to give you high resolution images. That means we will draw a bicycle, we need to really draw a very good bicycle. My goal in the neurals paper was for adversarial robustness. So maybe I don’t need to draw the whole bicycle, I just need to focus on the critical part. And there will be difference in the designing of this generative models because our goals are different. Asking the right questions will help us a lot and faster, that helps with communication. People know where you want to go to and they can give you the right suggestions.

Kanjun Qiu: Yes. I could not agree more. Are there any areas where you will be excited to see these areas develop over the next few years?

Yujia Huang: People talk a lot about reasoning is that maybe people want to build mathematical theory improver, or these symbolic AI stuff where we can learn some solutions analytically to a equation or something like that, and that’s the reasoning. It might also help in other fields, not just for symbolic AI, but vision or language. In general, I hope we can have these new components into deep learning. If we combine other components like attention and some other methods to make it to be helpful in someway like unified robustness or some way, this is kind of a replacement of the current forward only neural networks. If you can replace the things with these sort of dynamics with feedbacks, that could be called a reasoning, but we just need to provide a better definition reasoning. I will be exciting to see that the neuro networks can react more dynamically towards different goals, maybe for mathematical or for vision.

Kanjun Qiu: Are there any directions that you feel are promising in reasoning?

Yujia Huang: I’m not a expert on that. Yes, the open problem is test time adaptation, and maybe that’s different than what people call reasoning, because now if you search reasoning, maybe it’s more symbolic stuff.

Kanjun Qiu: Symbolic model.

Yujia Huang: But what I was trying to say about reasoning is that I hope during testing time, the neural network can still do something dynamically based on the environment. So it’s not a fixed dead thin, it’s a active thing.

Kanjun Qiu: That’s a good clarification. That’s what you mean by being able to adapt to different goals.

Yujia Huang: That’s what I mean.

Kanjun Qiu: Okay. Cool. The last question we always ask people is, are there any areas that you would like collaborators in, oh, be excited if people reached out about certain things?

Yujia Huang: Yeah.

Josh Albrecht: Or in the community, if you want people to send you particular papers, or if you have any ask, this is a good place for it.

Yujia Huang: I would be happy to collaborate with experts in deep learning because I myself works on deep learning, but I’m also very interested in collaborating with people in control, in signal processing and in neuroscience, mostly because of my work. This is a dynamical system, and now I’m modeling it through the lens of generative modeling, but you can also think of this problem in the lens of maybe using controls theory to model the dynamics of neural network, such that your neural network can be tuned towards some goal.

Yujia Huang: For a signal processing, if we model the high dimensional data, I think there is a lot of existing methods in signal processing that we probably can have. This is building inductive bias into the model. Those existing tools might be the right inductive bias that we can start with, and to adapt it for deep learning fields. For neuroscience tests, I want to ask them, what do they know about the brain and what do they think would be really reliable facts that we can build upon? Because I’ve talked with a lot of neuroscientists, about 80% out of 100%, I got the answer that they don’t know. I mean, there are joking but they were like, “We don’t know anything about the brain.”

Yujia Huang: It will be helpful for both fields to meet in trying to pin down something that we can really trust and work on those things. Of course, I’m also want to collaborate a generative model experts because the generative field currently, most of the people are focusing on generating high fidelity image. I’m very impressed by the progress in that field but not that many people are thinking about how to use generative models to do some other tasks classification. It will be good to talk with the experts who specializes in generative models.

Kanjun Qiu: Okay. Thanks so much for taking the time to be on the podcast. It was super interesting.

Josh Albrecht: Quite great.

Kanjun Qiu: I feel like I have 35 more questions to ask you because every time I ask you something, you surprise me, which is great. Thanks so much for being on the podcast. I hope you enjoyed it.

Yujia Huang: Thank you so much, Kanjun and Josh for having me here.

Josh Albrecht: Yeah. I really enjoy as well. It was great having you today. We’re looking forward to your next paper on NeurlPS in the next year.

Yujia Huang: Okay. Thank you.

Kanjun Qiu: Thank you for listening to Generally Intelligent. We love feedback and questions. So please feel free to ping us on Twitter at heart Kanjun and at Josh Albrecht, or email us with any ideas or corrections. If you enjoyed this podcast, please share it with fellow researchers, rate it on iTunes and follow us on Spotify, or your favorite podcast app. Thanks very much, and we’ll see you next time.

Thanks to Luke Cheng for writing drafts of this post and Tessa Hall for editing the podcast.